Elmer Chocolate combines tradition with transformation

Robert A. Nelson receives Candy Industry’s 75th Kettle Award.

Rob Nelson, chairman and CEO of Elmer Chocolate, received the 75th Kettle Award during a ceremony held May 24, 2022 at the Union League Club in Chicago. Photo by Cory Dewald.

75th Kettle Award recipient Robert A. Nelson poses with the copper kettle, alongside his wife, Virginia, and three of their four children after the ceremony at the Union League Club of Chicago. Photo by Cory Dewald.

Rob Nelson delivers his acceptance speech during the Kettle Award ceremony held May 24, 2022 at the Union League Club of Chicago while Kettle Committee members Elizabeth Clair and Denise Lansing look on. Photo by Cory Dewald.

Elmer Chocolate's former factory in New Orleans, photographed in the 1960s. A skyscraper exists at its former location today. Photo from Elmer Chocolate.

Elmer Chocolate employees pack pieces by hand before the company adopted automation throughout the operation. Skilled employees could pack up to 120 pieces per minute. Photo from Elmer Chocolate.

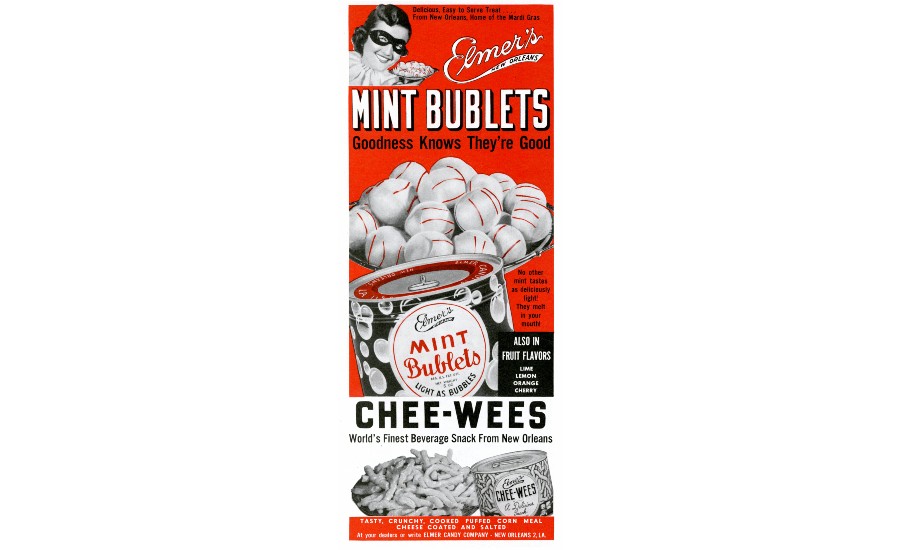

A selection of Elmer Candy products from the 1960s. Photo from Elmer Chocolate.

Like many regional candy companies, Elmer produced a variety of products in its early days, including Mint Bublets and CheeWees, a predecessor to the Cheeto. Photo from Elmer Chocolate.

Elmer Candy still makes the Louisiana staples of Heavenly Hash and Gold Brick, which are especially popular around Easter. Photo from Elmer Chocolate.

Elmer Chocolate has become one of the leading producers of Valentine's Day boxed chocolates in the U.S., thanks to its efforts to design boxes in house and warehouse its own finished products. Photo from Elmer Chocolate.

Elmer Chocolate makes thousands of pounds of seasonal chocolates each year. Photo from Elmer Chocolate.

Elmer Chocolate produces thousands of pounds of seasonal chocolate pieces during the year. Photo from Elmer Chocolate.

An Elmer Chocolate employee checks readings on the production line. Elmer has increasingly adopted automation as it has expanded over the years. Photo from Elmer Chocolate.

Tradition runs deep, and no one knows that better than Robert A. Nelson.

His home state, Louisiana, leads the United States in the percentage of current residents who were born there. From Mardi Gras and jazz, to gumbo and king cake, Louisiana’s food, music and celebrations are deeply rooted in long-held customs.

Elmer Candy Corporation is an important piece of the state’s heritage. The 167-year-old company is approaching its 60th year of ownership by the Nelson family, and Robert Nelson, who recently received Candy Industry's 75th Kettle Award, has been part of its leadership for three decades.

While Elmer still makes some of Louisiana’s most-loved confections, the company has combined tradition with transformation as it looks toward the future. By moving from New Orleans to Ponchatoula, expanding its operational footprint to 385,000 sq. ft., and increasing employment to 450 jobs, Elmer Candy has become one of the leading manufacturers of Valentine’s Day and seasonal boxed chocolates in the United States.

Early days

The company’s history begins with Christopher Henry Miller, a German immigrant who landed in New Orleans in the 1840s. He apprenticed in a pastry shop before heading to California during the Gold Rush to ply his trade. However, Miller returned to New Orleans in 1855 to found the Miller Candy Company.

Miller had nine daughters, and one — Olivia — married Augustus Elmer. Miller’s son-in-law ran the business, renaming it as the Miller-Elmer Candy Corporation. Around the turn of the century, the Miller name was dropped, and the business became known as Elmer Candy Corporation.

Nelson said many Elmers were with the company when his grandfather, Roy Nelson, purchased it in 1963. Roy Nelson, a Chicago native, had married a woman from New Orleans and worked with the Elmer family before buying the business. Roy’s son and Robert’s father, Allan, joined the company in 1965.

At the time, candy manufacturers made several types of confections for their geographical regions, and Elmer Candy Corporation had a strong foothold in the South, Nelson said.

“If you went to any of the grocery stores or drugstores, the whole section was Elmer,” he said. “They made all of these different products, and you had that in other parts of the country with other companies. It's really a textbook situation.”

Among the general-line products Elmer produced in the early days was Heavenly Hash, featuring milk chocolate, marshmallows and roasted almonds, and Gold Brick, a chocolate-covered pecan meltaway. Elmer still makes these Louisiana staples, which are especially popular around Easter.

“We still have to make it because if we didn't make it, we'd have crowds of people at our door,” Nelson said. “It's so engrained, even today. Most people in this area think that's all we do, and it’s a very small part of our business. It's something we do for about six weeks out of the year.”

The Elmer family also invented the corn curl around the Great Depression, adding cheese flavor to the product in the 1940s. The Cheeto predecessor received the name CheeWees, thanks to a naming contest submission. After a period of dormancy, the candy company sold the CheeWees brand back to the Elmer family in the 1990s, and Elmer Fine Foods — a separate snack company — manufactures the product in New Orleans today.

Moving and specializing

In the 1970s — facing dwindling space and aging facilities — the Nelsons opted to move Elmer Candy Corporation from New Orleans’ Central Business District to Ponchatoula, 50 miles northwest of the city in Tangipahoa Parish.

Nelson said a skyscraper now stands where the company’s old factory existed at Poydras and Magazine Streets in New Orleans. While he loves the city, Nelson said Tangipahoa Parish has been a helpful partner as the company has grown and transformed to meet modern food safety requirements.

“Everything, and certainly in the food industry, has evolved over the years from a regulatory standpoint,” he said. “It’s gotten more stringent, and you need to have the right facility to be able to run the organization you want to run…Tangipahoa has been part of the success, no doubt. We've expanded the company multiple times, and it's always been, ‘How can we help? What do we need to do?’”

Though he grew up around the business, Nelson joined the Elmer payroll as a teenager in 1983, doing everything from driving trucks and forklifts to working maintenance. He earned a business degree from Tulane University, helping his family’s company with sales and marketing during this time.

Nelson didn’t fully join Elmer’s ranks upon graduation, however. He enrolled in law school at Louisiana State University, with the goal of practicing law. Upon Nelson’s graduation, Allan asked him to help, just for a little while. Nelson joined the company as marketing director and general counsel.

“I'm a licensed attorney today,” he said. “I don't practice, but when I came out of law school, the company was experiencing a lot of growth. My dad — I remember him saying, ‘Hey, I just need some help, it could be a short-term option.’”

But for Nelson, it was never a short-term option. He loves the confectionery industry — and its people — too much.

“In the candy industry, I have competitors that are close friends,” he said. “In the legal world, I did not enjoy the same dynamic. Once you're in and you realize how special the industry is, there is no turning around.”

In the 1980s, Elmer pivoted from its general-line approach, opting to focus on boxed chocolates, particularly seasonal products. Initially, most of the company’s growth came during the Valentine’s Day season.

With packaging being one of its biggest concerns, Elmer Candy Corporation pursued a vertical integration route, designing and making boxes in-house and warehousing its own finished product. The cost savings realized by this approach allowed for more volume, and ultimately, more value for the end customer.

“When we first started doing it, we were worried about filling orders that first year,” Nelson said. “All of our orders for that year (are) probably about one or two days’ production here today.”

In 1995, Nelson became vice president and chief operations officer. Ten years later, he was named as the company’s president and chief executive officer.

Katrina and automation

The year 2005 wasn’t notable just because of Nelson’s promotion to Elmer Candy’s top job. In August, Hurricane Katrina barreled through New Orleans and the surrounding area.

While Ponchatoula is more insulated from brutal storms than New Orleans, Elmer still felt Katrina’s effects. Nelson, whose home was in New Orleans, said he didn’t return to the city for about a month after the storm. The plant, meanwhile, lost power for a few days, but it quickly resumed operations — which was welcome news to more than just the Elmer team.

“That first week, there were people lined up at the door looking for jobs, because they had just lost everything and needed a place to work,” Nelson said. “We were able to offer that, and then the government, the Red Cross, different organizations jumped in and filled that void.”

Nelson said many people from the hardest-hit areas moved to communities within 30 minutes of the Elmer plant, offering a greater pool from which to draw employees.

“It's like they just took a crane and picked up the town and moved it,” Nelson said. “It was a challenging time, but as a company, we have a good group of people that can learn quickly and move forward.”

And while it takes true skill to quickly pack chocolates into heart-shaped boxes — Nelson said the company had team members who could place 120 pieces in a minute without looking at their hands — the nature of the job has changed as Elmer adopted automation across the operation. As the work transformed with the times, so have the employees’ skill sets, Nelson said.

“That’s why we're in the candy business,” Nelson said. “We're a box chocolate company, but a lot of why we're here doing what we're doing is because we want to provide great jobs to people in our community. If you've got hundreds of people putting a piece of candy in a box, and you're saying, ‘Hey, we're giving you an opportunity,’ I don't know if that's really walking the walk…How do you talk about automation and having somebody that is operating the robot rather than putting the candy in the box themselves? There's a lot more opportunity.”

With greater efficiency, Elmer has increased its throughput, necessitating more shifts, and by extension, more jobs.

“If you're able to grow as a company, employment is only positively affected, and the jobs that you have are higher-paying positions,” Nelson said. “I like to dispel the myth, at least in what we do, that automation is taking jobs away. That's not my experience at all.”

Kettle Award and teamwork

Nelson said he never anticipated receiving the Kettle Award, but he’s been nominated twice — once in 2015 and again five years later. Like many previous nominees and recipients, Nelson felt disbelief.

“When I started in the industry, I would go to the Kettle Awards,” he said. “The people receiving these awards are people I look up to, people I emulated. I never ever dreamed that I would even be considered for something like the Kettle Award… The first phone call I ever got for a nomination, I was like, ‘I'm not in the same group of these people.’ To be nominated was awesome.”

Nelson, along with 2020 nominees Judy Hilliard McCarthy, former owner of Hilliards Chocolates, and Mark Schlott, executive VP and COO, R.M. Palmer Company, has the distinction of experiencing the longest nomination period ever. Candy Industry postponed the Kettle Award ceremony in 2020 and 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

While Nelson said he and the nominees joked that perhaps their grandkids could attend the ceremony, the postponements underscore how much changed during the pandemic, including the ability to travel to industry events.

“It made it that much more special than when it happened,” he said. “It represents a lot of different things, and two of them are just normalcy and the opportunity to be with good friends.”

Nelson said the Elmer team pulled together throughout the pandemic, completing their orders during two difficult years. The award, Nelson said, is not so much about the individual as it is about the accomplishments of the Elmer team.

“The Kettle Award is sitting right on our receptionist's desk when you walk in, and it says on there that the recipient is the team at Elmer Chocolate,” he said. “I'm grateful to have the team of people that I have here and that we've been able to do what we do. It's really a recognition of what we've achieved as a team. It’s very special to be able to share it with them.”

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!